If you google “reader loyalty” you can find plenty of online data. You’ll learn that “only 3.8% of readers are loyal, but they consume 5 times more content.” Or you’ll be told publishers have discovered the importance of loyalty because it “drives economic success.” But such breathless revelations belong to the world of digital commerce, where “publication” means website advertising and “readers” are merely website visitors.

For an author, reader loyalty has a different kind of value. It’s about the immense encouragement received from individuals who not only read each successive book that one writes but also respond personally by sending spontaneous messages of appreciation. Some of these unsolicited comments are brief; some are copious. Some may be from close friends; in other cases the bond is just a shared enthusiasm for literary storytelling.

As review space in newspapers and magazines continues to shrink, thoughtful comments that come directly from reader to writer are all the more valuable, especially when they reflect knowledge of the writer’s other work as a context for each new book.

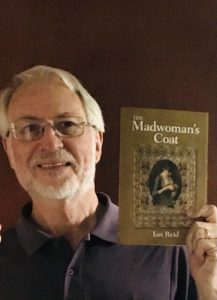

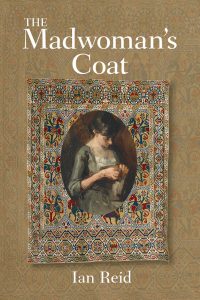

Not long after the launch of my latest novel, an uplifting email arrived from fellow writer Nicholas Hasluck, who knows my earlier fiction well.

I have just finished reading The Madwoman’s Coat and am writing to congratulate you on having completed a memorable work. The first few scenes at Fremantle in 1897 are compelling. I was immediately captured by the presence of various mysteries to be fathomed, including not only the motive and the underlying cause behind the death but also the creation and meaning of the embroidered coat. It was then very pleasing to be drawn further back to the lives of the principal characters in England and the aspirations of Lucy/Isabella and those around her such as William Morris and his acolytes. Thereafter, the various links in the chain of causation were skilfully fitted into place, leading on in due course to the dire events in Guildford and Fremantle.

As the story proceeded I felt constantly rewarded by the presence of the various elements to be found in the best works of fiction. The style, as in your other novels, was consistently graceful throughout and perfectly suited to the era and social settings portrayed. The mood thus created, a mood of elation at times, but also of desperation, especially towards the end, kept me in suspense along the way. In doing so, it pointed to and eventually accomplished a powerful resolution of the drama.

I feel instinctively that The Madwoman’s Coat is in the first rank. It is a fine novel and should be widely praised.

Soon afterwards, this cheerful message came from a former colleague, Prof Helen Wildy, who had expressed enthusiasm about each of my previous novels in turn and initiated book group discussions of several of them:

Is this your best ever? I think so, totally captivating, wonderful background stories all knitted (sorry, embroidered) together, and a lovely Icelandic saga underlying it all.

American literary critic Edith Moore has written to me at length about each of my novels as they have emerged. She reads closely and discerningly. Her extensive remarks on The Madwoman’s Coat are very gratifying:

Thank you for this wonderful and extraordinary novel! The focus on women’s perspectives is an inspiration, because it is a story of resistance and not of submission to fate. In the midst of trauma, past and present, we have Lucy/Isabella’s fierce responses to violence and the threat of violence. So often we are frozen when violence comes at us, and if we are fierce we’re called crazy. (I was thinking of Gavin Staines in A Thousand Tongues — was his inability to speak out a response to fear of his violent father? taking as a guide his mother’s “defensive taciturnity”?) But here is Lucy whose response to panic is to fight back, against the madman in the train while all the men are frozen, against the odious Dr Oram, against poor bumbling Alice. And quick to fight in defense of her art, against Julius, against Ruth Fitch, passionate in her last moments. Not submissive, and as Lucy/Isabella insists, not to be pitied.

Sad that her protective fierceness and fear of closeness keeps her locked away from Julius who seems a gentle and perceptive man. Would she have been able to see him without fear if he’d been less physically looming? If she had been able somehow in her mind to remove his mummer’s animal mask? Her efforts to understand her “perverse slighting of Julius” are impossible without looking clearly at her father, as she is beginning to see when trying to find a “justification for her reaction to Alice — at the time only the merest inkling of an explanation” which implies she does come to understand, does finally allow the memories to come out of the shadows.

And with the coming of full memory comes the glorious embroidery of the coat, and a story of creative fire refusing to be quenched. The “sparkle and exuberance” we see when she’s with the Morris family, the fire her aunt sees in her, are subdued but not put out. So fitting that on the very day that tears a ragged hole in her spirit, she is given a gift of beauty which will allow her to make necessary repairs in her soul, what she calls her “romance” with colors, fabrics and threads, her vision of a “sunny silken world” filled with bird color, flower color, sky, “pigmentary splendor.” And with her memory fully recovered she is able to gather the power of beauty into herself to sustain her soul, as Morris said Icelanders must do in their harsh landscape. So that she can transform the terror and ambivalence of her father’s transgression, her grief at the “interwoven miseries” of Julius and Gerard, into her own design, her story seen from kestrel height, with dancing mummers tamed into heraldic forms, and the image of Lucy at the center in control of the stag, made harmless with his antlers caught in Aesop’s blossoming tree. And couldn’t help but wonder if the silk mill is productive again.

When the magnificent parrot, image of beauty of freedom, flies into the room where the inquest is held and crashes into a window, the people flinch, and then forget. We can’t help but flinch when each new violent blow comes, but we don’t forget! Lucy says “in our art” there are “no illusions of permanence,” but as Tilly says, the artistry of the coat is “remarkable and lasting.” As is this beautiful novel.

Heartening comments have come from other places overseas as well, including the following from a loyal Danish reader, Dorte Huerlin:

Much to the reader’s satisfaction, Detective Inspector Rowe disentangles the yarn at the end, exposing poor Lucy/Isabella’s murderer. His own dramatic story was told, of course, in The Mind´s Own Place, also set in the Perth area. You fuse imagined lives with meticulously correct historical and geographic facts in a way I would call luxurious, Ian!

It must be so rewarding to dig into history in this way. You have the enviable talent and perseverance to carry out what I can only fantasize about… By far the best way of studying the past is empathising via narrative — your novels open the eyes of your readers to all the myriad individual destinies that founded modern Australia and New Zealand…

Lucy’s decoration of her coat becomes symbolic of a new type of male and female unison: the heavy gentleman’s overcoat, no doubt tailored according to the original military style of such garments, is softened by the imaginative decorative powers of Lucy, the craftswoman.

Andrew Taylor, a longstanding literary colleague whose encouraging comments on my novels go back to his reading of the first one in draft form, has sent this response to my latest:

“I’m immensely impressed… I’d like you to know how much I liked it and also how very very good I think it is. Your historical and cultural detail is not only convincing and detailed, it also serves to develop and consolidate the characters of the main actors and, of course, particularly Lucy. Your mastery of needlework is astonishing (I’d never caught you at it, so this was a surprise); what I mean is that the detail of this too is never superfluous, but contributes to the rich (like the embroidery) texture and tactility of everything. I was impressed, too, at how Lucy’s story avoids cliché at every crucial point — she’s impressed by the handsome soldier, up to a point, but in a far more complicated and interesting way than one would expect, and his character too is very subtly understood. And the way she evades being embroiled in his death and manages to escape to Australia is not only intriguing, even quite exciting, but also fully believable. I could go on and on, Ian, but these are my immediate impressions.”

And Melbourne-based Dr Michael Stanford, another person familiar with my previous books, made these comments about his experience of reading The Madwoman’s Coat:

I thought you were pretty courageous as a man writing a central female character but this worked well. One could only have sympathy for her plight throughout, even combined with mixed feelings about some of her behaviour…

I found myself accelerating through as the storyline became more and more gripping. I genuinely think this novel ought be picked up as a TV series or even movie because of its many interesting themes.

The combination of women’s place in society (and in the end victimhood), history, arts, two countries, treatment of mental health, the injustice of the legal system, love and death, all seems powerful to me.

A statement attributed to Ernest Hemingway asserts that “there is no friend as loyal as a book.” Still, there’s nothing more valuable to a writer, nothing more sustaining, than appreciative messages from loyal readers.