70 years ago George Orwell wrote a trenchant essay about the damaging consequences of waffle and jargon. ‘Politics and the English Language’ was a powerful statement at the time, and has lost none of its impact since then. In fact it seems even more relevant today because the trend that Orwell criticised is increasingly widespread: nearly every kind of organisation, public or private, has now become pervaded by clichés and empty slogans.

70 years ago George Orwell wrote a trenchant essay about the damaging consequences of waffle and jargon. ‘Politics and the English Language’ was a powerful statement at the time, and has lost none of its impact since then. In fact it seems even more relevant today because the trend that Orwell criticised is increasingly widespread: nearly every kind of organisation, public or private, has now become pervaded by clichés and empty slogans.

Orwell’s argument is that habits of careless communication contribute to a general blurring of ideas. We often fail to convey our intended meaning with proper precision, and this failure leads to vagueness about what exactly we mean anyway. So effects can reinforce causes. Our language, says Orwell, “becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.” Is this downward spiral inevitable, then? No. It can be avoided if we take the necessary trouble to communicate clearly. This isn’t a matter of pedantry. It concerns the lifeblood of a community’s wellbeing, as Australian writer Don Watson shows in books such as Death Sentence: The Decay of Public Language.

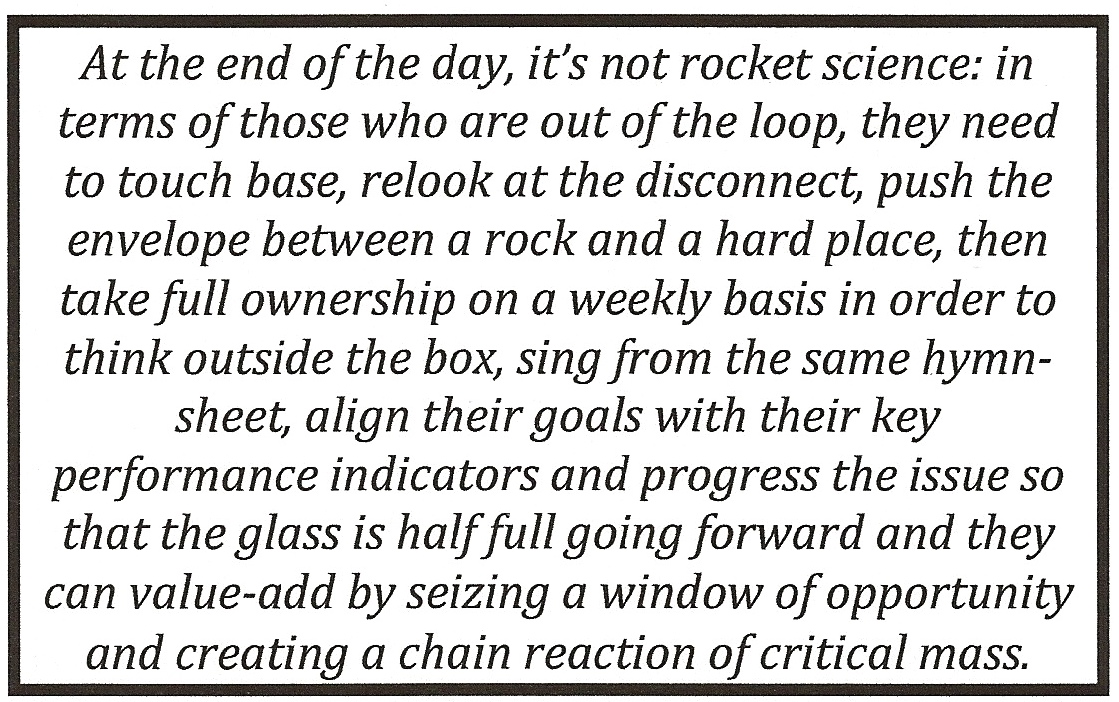

We’ve all encountered (and in our weaker moments we may have used) this slovenly kind of language, because most workplaces are full of it. Once it gets inside an organisation, remarks Don Watson, “it spreads like duckweed down every channel of communication.” As in the boxed sample below…

OK, I confess to writing this parody.

But aren’t the vacuous phrases depressingly familiar? And don’t they mess with our minds?

The “politics” of language, for George Orwell, isn’t confined to parliamentary contexts. He regards language as political in a broad sense that includes the way people speak and write within organisations. Pause for a moment and call to mind the tone and vocabulary favoured by senior managers in a workplace you know well. Now look at the following sentence, quoted from Orwell’s essay, and ask yourself whether the cap fits. “As soon as certain topics are raised, the concrete melts into the abstract and no-one seems able to think of turns of speech that are not hackneyed: prose consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated henhouse.”

And the result is…

Think for example about universities. As services such as education grow more market-oriented there’s a corresponding change in their use of language. The sociolinguist Norman Fairclough remarks that “this includes ‘rewordings’ of activities and relationships”: learners turn into consumers and courses into packaged products. The jargon of advertising and management invades teaching and research. To observe these trends isn’t necessarily to lapse into nostalgia for times gone by, or into an unworldly and simplistic idealism. Whatever the financial exigencies, those who work in universities must surely cherish the principle that clear thinking (which requires clear language) is what our academic institutions should uphold above all.

Just as common as those dubious “rewordings” are the many instances of glib rhetorical inflation in universities today – and in most other kinds of organisation too. It’s easy to get caught up in this devalued lexicon, and it has political effects because it dulls the brain, making us passive and pliable. Consider the flapping flag of “Quality” for example: underneath it, quality improvement (a worthy aim) slides into quality control (which may be less benign). Similarly, ordinary things get puffed up into slogans. Corporate hype can convert any half-baked notion into a “Strategy”, any hallucination into a “Vision.”

I’ve written at length about these matters in my book Higher Education or Education for Hire? Language and Values in Australian Universities. They continue to bother me. Lazy language, especially in organisational jargon, contributes to confused ideas and to what Orwell describes as “the worst follies of orthodoxy.” Much corporatised language is designed, he says, “to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind. One cannot change all this in a moment, but one can at least change one’s habits, and from time to time one can even, if one jeers loudly enough, send some worn-out and useless phrase…[he gives examples – but supply your own!]…into the dustbin where it belongs.” Such irreverence ought to characterise any principled academic community.

“Phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated henhouse” – perhaps you, dear reader, have spotted some of these in your working environment, and would like to share them through the comment box below?

And another question: Is it unduly optimistic to think that there may be a special role for creative writers in the noble cause of resisting lazy language ? I’d be glad to think that those who write inventively, with a disdain for moribund clichés and a skill in choosing lively words, can at their best help to clarify and energise the thinking of their readers. George Orwell himself surely did so, being not only a great essayist but also the author of such challenging fictional narratives as Animal Farm and 1984, which imagine the political consequences of debased language. We need more writers like him.